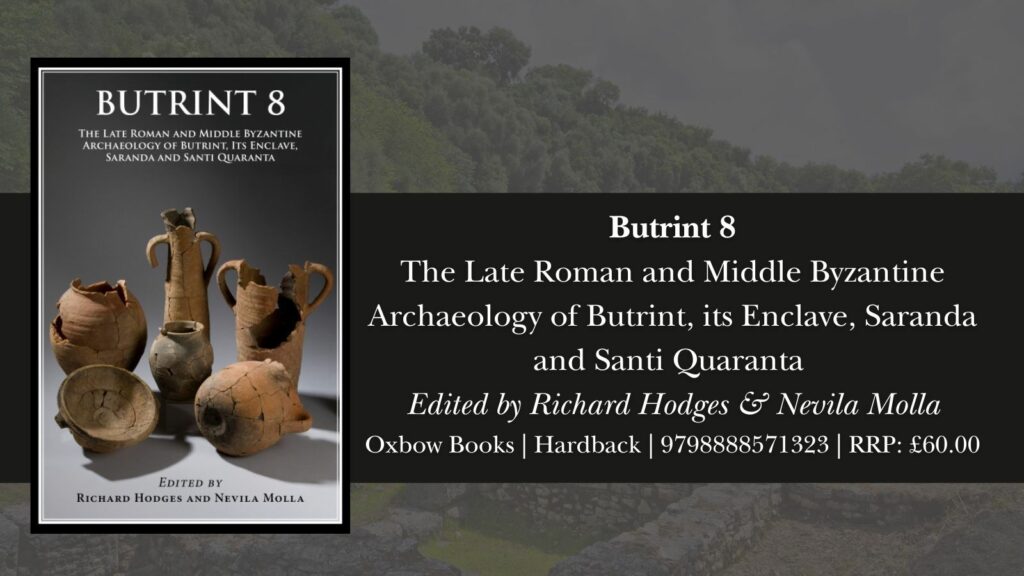

Want to know more about the latest volume in the Butrint Archaeological Monographs series? This blog by Richard Hodges, co-editor of Butrint 8, is bursting with insider information on the excavations explored in the book, which “aims both to report archaeological discoveries and to provoke a rethinking of some important episodes in Mediterranean archaeology.”

By Richard Hodges | 4 min read

This in the eighth book in the Butrint Foundation’s Archaeological Monograph series (although Butrint 6 consists of 3 volumes). To these we should add two monographs (on Butrint’s Hellenistic and Roman theatre and the Cardini archives relating to Butrint’s palaeolithic archaeology published with the British School at Athens). Thanks to the Butrint Foundation, created by Lords Rothschild and Sainsbury in 1993, this Ionian seaport has gone from comparative obscurity to being a benchmark for Adriatic Sea and Albanian archaeology. More volumes relating to the 1994-2012 campaigns are being presently prepared. In all, the aim is to do justice – something rarely done in Mediterranean archaeology – to the privilege of carrying out fieldwork in such a remarkable place.

This book is dedicated to the memory of Kosta Lako (1949-2021), the Saranda-born archaeologist with whom we began our collaboration at Butrint in 1994. Kosta excavated and published his research at Butrint, Çuka i Ajtoit, Saranda and in a preliminary way, the great Late Antique ruins of Santi Quaranta.

The volume contains a detailed report on the remarkable excavations in the Western Defenses, reappraising earlier interpretations on the basis of a short campaign in 2022. Tower 1 was destroyed by fire in about AD 800, while Tower 2, which had a similar stratigraphic sequence, continued to be used until the later 9th century. The finds include an important 9th-century glass collection that is published in full.

[T]his Ionian seaport has gone from comparative obscurity to being a benchmark for Adriatic Sea and Albanian archaeology.

Butrint 8 contains a report, too, on excavations around the Great Basilica, illustrating the episodic and long story of this important part of Butrint overlooking a major 1st-century road bridge.

A chapter is dedicated to Butrint’s hinterland, ranging from the Dema wall – a Greek frontier wall refurbished in the Mid Byzantine era as well as by the later Venetians – to the settlement on the Vrina Plain outside Butrint with an exceptional 12th-century rubbish midden full of finds, and finally the fortified hilltop at Çuka i Ajtoit, which is now believed to have been a Mid Byzantine rather than a Late Roman stronghold (as well as an Archaic Greek and Hellenistic citadel) overlooking the coast road.

Four chapters are devoted to Saranda, ancient Onchesmos, with the aim of putting the archaeology of this small Roman and later port on the map. An overview of the archeology prefaces a reappraisal of the port’s main Late Roman Basilica, which had previously been a synagogue in a townhouse. There then follows a short report on rescue excavations made in the port by the Butrint Foundation, which includes a study of the coil-made, so-called Slavic wares found here as well as at Butrint (and more widely in Epirus).

[T]he aim is to do justice […] to the privilege of carrying out fieldwork in such a remarkable place.

The fourth chapter in this section is a major study of the hilltop sanctuary at Santi Quaranta, a truly remarkable site dedicated to the 4th-century 40 martyrs of Sebeste. Blown up in 1967 or so, when all religions were banned in Albania, this report phases the remaining structures and proposes that it was a major healing centre in Late Antiquity. The new survey begins by hypothesizing that a Roman temple first occupied this spectacular site overlooking the Ionian Sea. Then, in the late 5th century the great sanctuary was made, with remains of tile-made Greek inscriptions set in its walls. At least ten donors were involved. The sanctuary was then remodelled in the 520s opening it to pilgrims, when a new west front and stair were added. In the labyrinth of well-preserved crypts below wall paintings depict the process of healing through incubation close to the cult. In this telling, the processions to the cult are vividly reconstructed. The sanctuary was then struck by an earthquake in the later 6th century. The 7th-century phase is remarkable for its downsized and primitive form before it was abandoned, only to be reoccupied in Ottoman times, and again in the 20th century. Still considered a holy site, this is one of the great places in Late Antique archaeology and now, thanks to this report, it is on the academic map. The next step, in the face of rampant hotel building at Saranda, is to use this report to ensure it is conserved properly.

The volume ends with a discussion of the Late Antique and Mid Byzantine archaeology as society and the economy around the Big Sea – the Mediterranean – collapsed, to be revitalized with Byzantine state support around the turn of the millennium.

The volume concludes with an interview of Dr. Dhimitër Çondi, an archaeologist from Saranda who has been active at Butrint and its surroundings for more than fifty years.

Butrint 8 aims both to report archaeological discoveries and to provoke a rethinking of some important episodes in Mediterranean archaeology.

Butrint 8 is available now from the Script Books website.

Featured image: Butrint, Albania. Credit: Robs123 from Pixabay

Follow

Follow